I was brought up in Bream in the Forest of Dean which was a pit village up to 1962, when Princess Royal Colliery closed. Up to this time, the women in the village took all responsibility for the domestic work, including childcare, cooking, baking, feeding, shopping, cleaning, washing, making and mending clothes and, before the introduction of pit head baths in 1939, providing a bath for the men and boys as they returned from work, as well as looking after the children. The men expected a meal on the table before and after their shift in the pit. The women had to manage their receipts from the weekly wage packets, making sure there was money left over for rent and bills.

The day often started at 4 a.m. with lighting the fire and cooking breakfast for the men, boys or lodgers on the early shift. Then meals and baths had to be prepared for those returning from their shift. The three-shift system, including night-shift, meant that women could be working a seventeen-hour day. Monday was washing day but for large families, the task could take several days. Washing involved hand-cleaning dirty sheets and clothes thick with dirt, coal dust and sweat. It was back-breaking work, filling a heavy cast iron boiler with water over the fire and then carrying boiling water to the zinc bath, washboard, rinsing tub, starch bowl, mangle and clothesline in the backyard.

Ian Wright

“My home life was very very hard times, my mother was left a widow when my father died. I was two years old then. She was left with seven children.

There was no dole, no income whatever. She brought us up practically, they call “on the washtub”, doing work for other people. It was very hard times”.

Forest of Dean miner Harry Toomer (1902 -2004)

Harry Toomer was interviewed by Elsie Olivey and Helen Nash on 9 February 1984

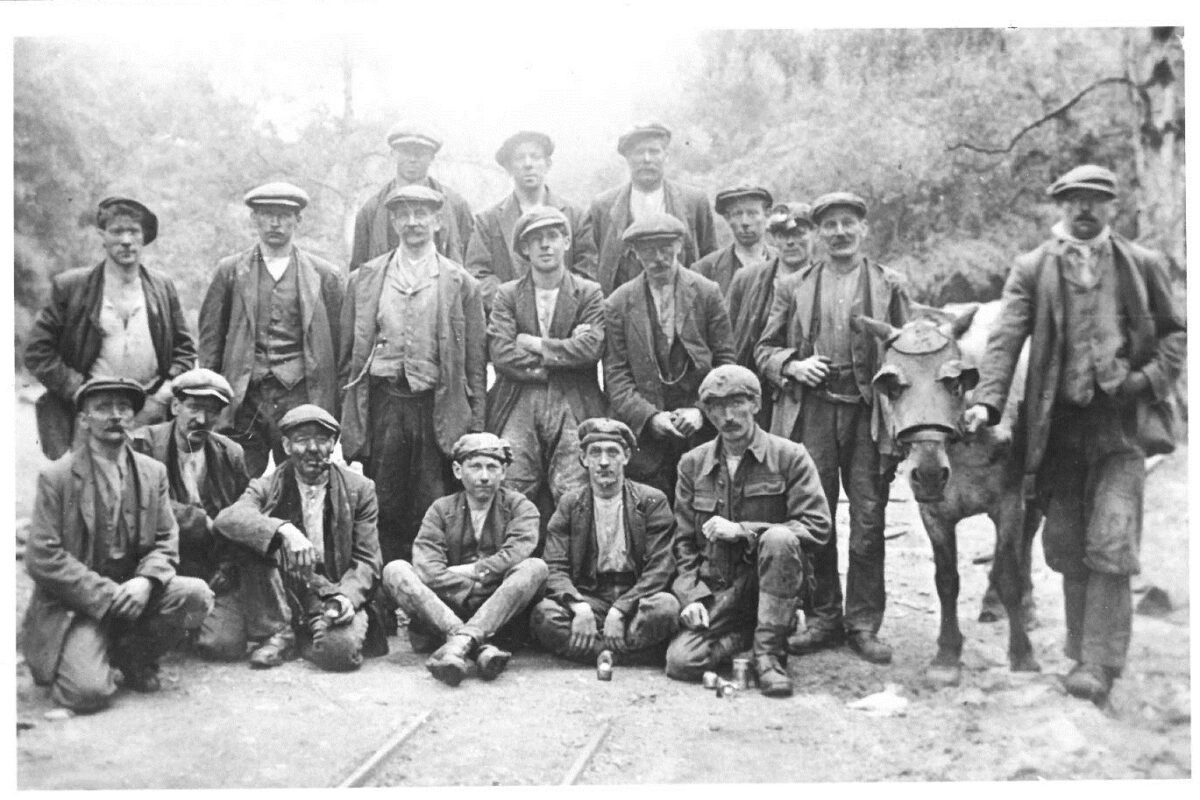

Credit: Gage Library, Dean Heritage Centre.

“Washing day always had a smell of its own. Mum always used Lifebuoy soap as there were no soap powders then. The kitchen would be full of steam if it was a wet day and wet clothes would be everywhere.

It was hard work in those days as you had to get the dolly tub out, fill it full of hot water, beat the clothes with the dolly for some time, take them out all dripping wet and put them through the mangle which was kept in the cellar, as it was a big awkward thing. Then more cold water was put into the boiler and all the white clothes boiled up until clean. Then they were put through the mangle again.

Most people did their washing on Mondays and if it was a fine day you could see lovely white clothes blowing in the wind in some gardens. Tuesday was ironing day. The flat irons were heated up on the stove or the fire and so had to be cleaned before using them. You had to put them up to your face to feel if they were the right temperature before you could iron the clothes.”

Freda Phipps nee Morse (1912-2000) from Early Days at Stone Cottage, Yorkley, Forest of Dean by. Credit: Forest of Dean Family History Society.

Washday 1919

My father was a great one for organisation and timekeeping, despite his blindness. Every morning he would be out in the scullery, stripped to the waist, and having a good scrub down. Then breakfast in the living room where mother would be frying bacon and eggs on the black stove with which she had been wrestling from an early hour. We would be rushing around getting ready for school and having our breakfast. In the pram the baby would be trying to command attention. By the time we were out through the front door on our various ways, Dad would be at the rug-making frame, hard at work.

Mondays were more demanding still on my mother as, in the time-honoured tradition, this was washday. The old copper in the corner of the scullery had to be filled with water and a fire lit underneath; an even more tenuous operation than the stove in the living room. Still one had to persevere with it as there was no hot water to commence the washing until the monster began roaring. A large tin bath was filled with blue water for the final rinse and kettles boiled on the stove for making bowls of starch, considered essential.

My father had bought a modern luxury supposedly designed to lighten my mother’s labours on Mondays…a mangle. This huge instrument stood well above my mother’s head, was built of cast iron with huge wooden rollers. On one side, an enormous wheel with a handle to turn the rollers. And on top a smaller wheel to screw the rollers together, or to loosen them when not in use.

The clothes were washed in a dolly tub in soapy water, dollied vigorously with a wooden dolly and white cottons boiled in the copper. The garments were immersed in another container of cold clear water, well rinsed and put through the mangle. My father would come in and help out with this operation. He would screw down the rollers and, as Mam had not sufficient reach to feed the clothes into the rollers while turning the wheel, he would do this for her as well.

Another zinc bath would be standing on the floor in front of the mangle to receive the flood of water which came gushing out while the garments, flattened into board-like shapes, came peeling out at the back. If the day was fine Mam would pile these into a washing basket, climb the high stone steps to the back garden and hang them on the line. Most of the colliers’ wives would already have lines of washing flapping in all the back gardens all over town.

Going back down the steps, Mam would take the whites, which had been boiling merrily, from the copper, and start once more on the rinsing, blueing and starching routine. Dad would be called in once more to lend a hand.

Incidentally, the baby would have been bathed, dressed and hopefully put to sleep. When we all rushed in, hungry for dinner, Mam would be glad if she had managed the bulk of the washing and had the cloth on the table with the cold Sunday joint, cheese and pickles. Every other day we had a hot dinner, but everybody accepted that Monday was washday. I hated Monday dinner. I didn’t like cold meat and hated pickles, not realising at this age how I added to my mother’s problems, I complained bitterly.

My father had a hearty appetite, loved strong cheeses and a variety of pickles. One Monday I remember he told me to shut up moaning, and offered me sixpence if I would eat a pickle he choose for me. I pondered the offer for a while, then thought of all the choice there was with a whole sixpence, and accepted. My sisters were loud in their protests. Had they not eaten all their meal and had no reward? Dad merely grinned and told them to shut up. He then presented me with a large red peppercorn. [chilli pepper by the sound of it]

My sisters, more familiar with the varying taste of pickles than I, who had refused to sample them, gazed at me wide-eyed. I bit the end of the red object. Not only did it smell and taste vilely, it was burning hot on my tongue. I swallowed it quickly and took another bite. Eventually I ate the whole of it, rushed into the scullery and swallowed cold water. Back into the living room. My father handed over sixpence and I said, “Good afternoon” as we always did, and went out into the street.

When my eyes had finished streaming I made my way along the street fingering my riches. I decided on a large block of Cadbury’s Nut Milk Chocolate, the ultimate in luxury. I went down Foundry Lane, breaking the squares, sucking the chocolate from the nuts, then delightedly crunching the crisp kernels. Halfway through afternoon school I had to rush out and was violently sick, then had to sit in the corner with my head on my arms until closing time. I can’t remember having any feelings of resentment. I had made a bargain and kept it, and after all still had half a block of nut milk chocolate to be nibbled when I felt more like it. [Not sure if dinner mentioned above was lunch, or if the chronology became confused some other way.]

When we came home from school we sat around the table for tea, the table being covered with a starched white cloth…one product of the mammoth washday session. When I say white, you could almost tell the day of the week from the appearance of the table cloth. Starting at Sunday tea-time when it appeared newly laundered, stiff as a board, sharp creases running longitudinally in the correct manner, it proceeded through stages of spots and dabs to a limp travesty of its former glory. Only when drama intervened in the guise of an overturned cup, or worse still upset gravy, was the cloth replaced by a clean one in the week.

It was not the lack of table cloths, we were well supplied with those, but the time-consuming labour of their maintenance. Boiled with soapy water and soda in the copper, rinsed and rinsed again, put through the blue rinse and finally starched, mangled and dried, they still demanded attention.

My mother had to enlist one of us girls to take one end while she took the other. You had to gather the material levelly between your fingers, stretch the linen between you. from one end of the room to the other, and do a sort of jiggling movement to straighten the threads. You then opened the cloth to full width, folded corners together in time with your partner, same again, hold the now quarter width high in the air, advance to meet your partner. It was all quite like the measured steps of a dance.

Then Mam would take over, see that the dampened spots were evenly distributed, roll up the long length in a tight tube, then leave it to become evenly damp all through.

Meanwhile the stove would have been coaxed into an evenly glowing red, and the heavy flat-irons set to heat up. The table was covered with blankets and sheet, bath brick and cloth at the ready to keep the surface of the iron well-polished. Then to work… a large wicker basket piled high with folded laundry awaited.

Sheets, pillowcases, towels and underclothes all had to be ironed. But the most demanding, which had to have just the right temperature, the most polished iron, were the table cloths, and Dad’s shirts and collars.

You had to take the iron from the fire, hold it near your face, spit on it to see if, when the globule hit the surface squarely, it immediately bounced off sizzling. A final rub with the brick cloth, a further test on some dampened material to see if the result was correct, then get going. The most shattering hazards of which to be wary were a too hot iron which resulted in a scorch mark, or a smoky smut which had slyly attached itself to your iron, and resulted in a black blob on the pristine surface. Certainly washday in 1919 was no easy process.

Gladys Duberley (1911-1988). Credit Nick Duberley and Gage Library in the Dean Heritage Centre.

(Not everyone worked in the mines. Gladdys’s husband was blinded during World War One and worked at home making mats, so was able to help with the washing)

More of Your Stories

Washday in Yorkshire

I grew up with my two sisters in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in a…

Tony Wilson’s Laundry Memories

I’ll Be with You In Apple Blossom Time

Stories recorded by Pauline

Pauline recorded some lovely visitors’ stories at the Watershed prototype showcase event and also at…